Offensive Evolution (Part 1)

Posted by Andy on June 17, 2010

"Offensive Evolution" is going to be a series of relatively short posts looking at how offense among regular players in baseball has changed through the years. This series was inspired by the discussion in the comments on a recent post. Click through for Part 1.

Recently we discussed how common it used to be to see some great-field, no-hit players who get enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title. In the 1980s and 1990s we saw guys like Ozzie Smith and Omar Vizquel who, while not "no-hit", were among the weakest players with the bat but played every day thanks to the value of their defense at shortstop. No doubt we can come up with countless examples, especially the further back in time we go, of players whose primary value was with the glove.

Starting in 1993, the notion that positions C, 2B, SS, and CF were primarily defensive positions got turned upside down when players such as Nomar Garciaparra, Ivan Rodriguez, Jeff Kent, and Ken Griffey Jr. started putting up very strong offensive seasons. Soon it became the norm for teams to have some of their best offensive players at some of those positions. At the same time, the every day player who was in the lineup for his glovework and despite his bat became scarce.

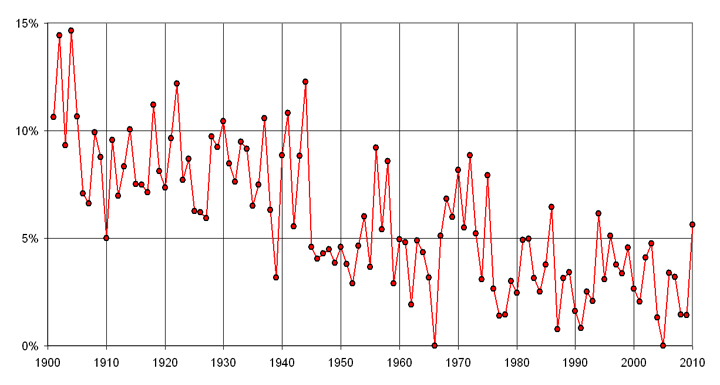

This reality, along with an overall greater trend, is illustrated in the plot below., which shows the fraction of players each year (among those qualified for the batting title) with an OPS+ under 70. These days, we don't see many every day players with OPS+ values under 70, but it was more common the further back in time you look.

In the early part of century, more than 10% of everyday players had an OPS+ below 70. From 1910-1940 it stayed roughly constant around 8-9%, with some bobbing up and down. From 1945 to 1952 the number of qualified batting seasons took a sharp downturn, and the variation of those under OPS+ of 70 was a lot smaller. I'm not sure why the # of qualified seasons went down but the most likely answer would seem to be war veterans returning to the majors part-time and/or frequent substitution of less talented players who were attempting to fill in.

Anyway, since then, the fraction of players with <70 OPS+ seasons has, on average, dwindled. It hasn't been over 5% since 1996. (You can for all intents and purposes ignore the 2010 number of about 6% since it's unlikely this year's culprits will all finish below 70 or with title-qualified seasons.)

I believe there are several factors that contribute to this overall decline in players below 70 OPS+:

- Overall player talent has improved: as the overall talent level of major-league players improves, there will be fewer who vary from the middle as much. Fifty years ago, conditioning varied a lot. So did quality of scouting. The best players from then are probably quiet comparable to the best players of today in terms of talent, but the average player is more talented today. This means a smaller standard deviation in numbers like OPS+ and even though 50% will still be below average, they don't range quite as much below average. Another way of saying this is that the difference between the best player and worst player is smaller today than it used to be.

- Less variation in defensive ability: Equipment like gloves used to vary a lot. Quality and consistency of playing fields used to vary a lot. As equipment and fields have become more uniform, the amount of variation in defensive value of players has shrunk somewhat. This means that there are fewer and fewer players worth playing every day just for their defense. (Overall athleticism also contributes to less variation in defensive ability.)

- More emphasis on offense: I don't think managers think offense is more important, necessarily, but as offense has increased, it's clear that a few 3-run homers from your shortstop might be worth more than what he gives up if he's not the best defensive shortstop in the league. Obviously both sides of the equation matter if you want to score more runs than you allow, but when it comes to evaluating individual players, I think the tendency is to believe that a guy who can hit a little is worth at least as much as a guy who has excellent defense. Right or wrong, I think this leads to fewer glove guys getting full-time gigs.

- More efficient use of talent: General managers and managers have learned over the years to give more and more plate appearances to their best all-around players. While we used to see defensive whizzes get regular at-bats we now tend to see the best hitters batting every day while the defensive aces come in as late-game replacements. There are many exceptions, but the bottom line is that even though the defensive guys play, they less often get enough plate-appearances to qualify.

Much more to come on all of this in the rest of the series.

June 17th, 2010 at 8:29 am

Interesting post. As for the drop in the post-WWII years, I think you're implying it, but I believe the main reason for it is that platooning became far more the norm than it had been. That put more players, even weak hitters, in situations where they could get over the 70 mark; more importantly, it pushed them under the 477 (later 502) PA mark.

June 17th, 2010 at 9:07 am

OH CRAP - I had a long post with many links just go bye-bye...

Anyway, my case is that the power surge, at least among middle infielders, began a little earlier. 1993 was when it became more mainstream, but Joe Morgan's 1972-1976 is the beginning of a real trend towards more offensive production from second and short. Bobby Grich had a similar but more walks-driven stretch at the same time in Baltimore, and then went more for power in California in the early 80's. Cal Ripken Jr, Alan Trammel, Lou Whitaker, Robin Yount, and Ryne Sandberg were strong hitters throughout the 80's; Barry Larkin and then Roberto Alomar followed them as the 80's turned to the 90's. I may be forgetting a few examples, but that only shows that there were enough examples to have people get overlooked.

June 17th, 2010 at 10:14 am

Could it also have to do with the way players are developed? I'm 26 and grew up playing ball. Almost every team featured their best player and athlete somewhere up the middle, usually SS or CF. These were the hardest positions to play and, thus, coaches usually put the best athlete there as well. Obviously, there is intense weeding out and players moving to other positions as they are less able to rely simply on pure athleticism and/or their body changes, but it seems like if we're starting with our best players/athletes up the middle, you would logically conclude that you'd seen a healthy boat of talent moving through those positions. And if this wasn't always common practice, it might be a factor as well.

Of course, if it WAS always common practice, simply ignore what I wrote...

June 17th, 2010 at 10:30 am

I find it strange that your doing 70 OPS+ as a percentage of the league. Isn't OPS+ based on league averages? So the guys who are hitting 70+OPS are a part of the equation of that sets there particular stanadard OPS to a value of 70 OPS+. So for every guy who has an OPS + less than 70 there is (and this logic definitely doesnt hold true but just bear with me) at least 1 other player with an OPS of 130. In fact if their were just 2 players in the league and one guy had an OPS of 70 wouldnt the other guy have an OPS of 130? Again this is way simplified im sure and it's also early and I haven't had my coffee.

I won't argue that all-glove no-hit players are less common these days. But, what I gather from this plot is that the level of greatness is slowly trending downward and all players are more centralized. Increased training regimens and players being molded at a young age to become baseball players has made the competition quite saturated with greatness. Whereas, back in the day (not sure when you would start "the day" but i would say pre-expansion at the latest) it was much easier for a player to stand out amognst their peers.

These are just my opinions... not bashing on Andy's post.

June 17th, 2010 at 10:32 am

Looks like I just rewrote the second half of andys post. My bad

June 17th, 2010 at 10:34 am

Jim, your intuition is correct, but the results don't turn out as you expect (or as I expected either.) But even if you were correct, that result alone would be interesting, to see that players tend to be clustered around OPS+ of 100 rather than having more outliers in both directions.

June 17th, 2010 at 10:38 am

I believe that the evolution of the offensive-minded middle infielder began even earlier than Nightfly implied; albeit a beginning that only reached significant proportions by the early Seventies. Players like Schoendienst, Gilliam, Runnels, Stephens and Banks began the surge, while players like Cardenas, Mazeroski, Maury Wills, Rico Petrocelli and {of course} Pete Rose came to prominence in the Sixties. Even the "average" middlers {my personal hero, Cookie Rojas, among them} fit less into the "Good Field, No Hit" model.

June 17th, 2010 at 11:00 am

I think I can see your point, Frank, but I have to disagree. I was thinking of guys who could really drive the ball rather than singles/doubles types like Schoendienst or Maz, or fast slap hitters like Wills. Stephens and Banks of course were mashers - perhaps the first - but they were exceptions until the 70's. Schoendienst and Runnels were never full-on power hitters, though they weren't useless at the stick. And Maz was also a great glove man, or I don't know that he would have stuck for long - he was below-average in OPS+ every single year he was in baseball.

Rose only broke in as a second-baseman - he was moved to the outfield and the third base fairly quickly, maybe five years, and in any case, is more in the Schoendienst mold as a hitter, rather than Stephens or Banks.

June 17th, 2010 at 11:01 am

There will always be the statsical outlier who can hit at a non-offensive minded position. The best examples is Rogers Hornsby, who hit over .400 and has a lifetime average over .300 (well over that actually), all at the lowly position of second base

June 17th, 2010 at 11:23 am

Even long before the 60s you had very strong hitting middle infielders. Rogers Hornsby played 1500 games at second base and 300 at SS out of 2100, and Honus Wagner played 1800+ games at shortstop. There have always been strong bats in the middle infield. What's declined to almost nothing is the number of guys playing everyday with well below average bats. It used to be you'd see a few guys playing up the middle with solid bats, and if they were not liabilities in the field and played 15-20 years, they'd be hall of famers, because most of the people playing their position were below average bats. Now, you have some defensive specialists, but except for the occasional guy like Vizquel, who is good enough defensively to get some hall support *and* not that far below average with the bat (only 2 of his 22 seasons would he be on this chart), they rarely play every day for a whole season.

the hall monitor should adjust for this if the voters start to. Right now it gives a lot of credit for just playing games at the key defensive positions C/SS/2B/3B/CF. If the voters adjust their expectations in the same way that GMs and managers have, those credits should get a fair bit smaller.

June 17th, 2010 at 11:30 am

Honus Wagner was the other middle infielder I was thinking of, thanks for picking him up

June 17th, 2010 at 12:07 pm

Shame of shames! I forgot all about Wagner and Hornsby. {Standing int the corner with nose against wall}. I also forgot the granddaddy of slugging middlers {a term I borrowed from the Sunday School class my wife teaches}, George Wright.

June 17th, 2010 at 12:10 pm

Hey, stop harshing our narrative with your facts, maaaaaaan!

June 17th, 2010 at 12:10 pm

Read this piece recently ( http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/14/a-labor-market-and-baseball-mystery/ ) where an economist surmised that the trade off is between more doubles & homers (with the bat) v fewer singles (with the glove). In low run-scoring environments, the extra XBH with the bat (fewer baserunners, greater chance of being stranded after double) are worth less than the singles saved with the glove with the opposite true in high run-scoring environments.

Squinting at the chart, oyu can see that while the trend is down there are adjustments by era. The 30's are trending down and the 60's are trending up.

June 17th, 2010 at 12:19 pm

I didn't read the article, but that's backwards. Slugging is relatively more important in low-scoring environments, and OBP is relatively more important in high-scoring environments.

June 17th, 2010 at 12:19 pm

Anon, does this mean that if someone could ever balance the budget, he should be signed by the Yankees?

June 17th, 2010 at 12:19 pm

I think some people here are missing the point.

The point isn't that there were never people who could hit at these "non-hitting" positions, but rather that there used to be a sizeable number of people who couldn't hit at these "non-hitting" positions.

So coming up with examples of people who could hit at these positions doesn't disprove Andy's point at all.

June 17th, 2010 at 12:22 pm

Matt, you're right, but I don't think people are arguing with my original post that way, exactly. Keep in mind that what I wrote above was intentionally oversimplified for the sake of writing a readable blog post. I could go on and on and on for 5 pages if you prefer...

June 17th, 2010 at 12:32 pm

No, I was not contending with Andy's original poit. What I was saying was that, rather than an abrupt revolution in which we suddenly got offensive-minded Middlers {I'll still employ the term}, the move to getting offence from the middle infield was an Evolutionary {not REvolutionary} event, taking a few decades to come to fruition; a development, rather than a sudden occurance.

June 17th, 2010 at 1:15 pm

Not to be on the defensive but I was simply pointing out that there were statistical outliers, such as Wager and Hornsby who didn't fit the mold.

June 17th, 2010 at 2:26 pm

Jim, I likewise agree with you.

And, among those "outliers", we have forgotten a rather significant one -- the Mechanical Man, Charlie Gehringer. A true five-tool player.

June 17th, 2010 at 2:47 pm

Perhaps a less confusing and more focused way to get to at least part of the trend Andy is identifying is to point out that, with just a couple of minutes of spot checking on b-ref's league batting splits, I see that the tOPS+ for all NL shortstops was 96 in 2009, 92 in 1989, 85 in 1979 and 77 in 1969. I only checked those few years, and a more comprehensive review would be needed to say anything definitive, but just those few data points seem to show a very emphatic trend that I think Andy is trying to show.

June 17th, 2010 at 3:30 pm

Birtelcom, good point. Actually I wrote a detailed post on this a couple of years ago. It shows tOPS+ split out by position and shows how much less variation there is these days than years ago.

This is a good post, folks, check it out:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/blog/archives/921

June 17th, 2010 at 4:26 pm

My guess as to why shortstops tend to be more competitive as hitter these days is that with the increasing frequency of Ks, BBs and HRs, and the relative decline of the frequency and importance of balls in play, the relative importance of shortstop defense has declined. It's still important, of course, but less so than it used to be. As the relative importance of shortstop defense has declined, scouts and GMs are more likely to choose a SS who can walk and hit homers even if that means compromising a bit on the defensive side. As Bill James has pointed out, over the decades bats have gotten thinner-hnadled and lighter and thus easier to whip around, increasing the number of homers and Ks, and reducing balls in play. Indirectly that same development probably encourages more offense at shortstop.

June 17th, 2010 at 7:00 pm

Is there a way to calculate the effect of changing ballpark distances on this? I ask, because I would think that even shortstops have less demand on them with the closer fences and better-designed parks, as opposed to fields where the outfield distances were greater, and the general condition of the fields was less consistent.

June 18th, 2010 at 7:54 am

[...] in Part 1, we saw that the fraction of qualified batting seasons with an OPS+ below 70 has gotten generally [...]