Offensive Evolution (Part 3)

Posted by Andy on June 21, 2010

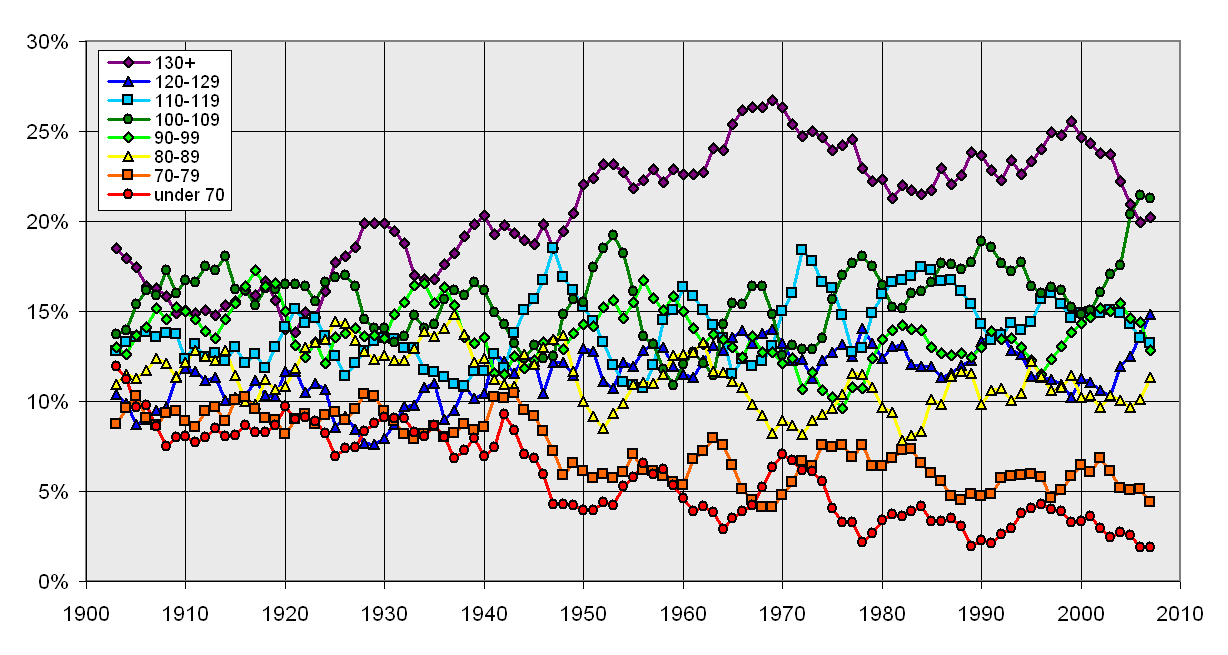

In the concluding part of the series, we look at how all OPS+ levels for regular players have changed over the years.

If you didn't see Part 2 of this series, start there, then come back to this post.

Let's start right off with the full graph:

(There is a lot of data here. Please click on the image to see it full size.)

This graph shows the fraction of all batters each year (among those qualified for the batting title) whose OPS+ fits into each of the given categories. The purple (top) and red (bottom) lines are the same ones we saw in Part 2 of this series, except that I have applied a 5-year average. In other words, the data points for 1950 (for example) are actually the average percentages from the years 1948 to 1952. That's why the graph starts in 1903 (using data from 1901 to 1905) and ends in 2007 (using data from 2005 to 2009.) I have removed 2010 from this plot, and all the new data sets are averaged in the same way as I just described.

Notice that from 1900 to about 1925, the overall amount of variation between qualified players of different OPS+ values was fairly small. Generally each level of player was somewhere between 7 and 17%. This means that for each everyday player with an OPS+ below 70 there were roughly 2 everyday players with an OPS+ of 130 or better. That's a surprisingly small range as compared to modern times, when there are at least 5 times as many 130+ regulars as there are <70 regulars.

Other notes about this graph:

- Players with an OPS+ from 70 to 79 and qualifying for the batting title have suffered a similar fate as those under 70. They have decreased in prevalence steadily, nearly as much as the players under 70.

- An OPS+ of 80 seems to be the cutoff. Players in the range of 80-89 haven't changed much, falling by just about one percentage point, on average, over 100 years.

- In fact the entire range of 80 to 99 hasn't shown all that much change over the years.

- The group at 100-109 OPS has had a lot of ups and down, including an 'up' in recent years that has this group as the most common in baseball for the first time since the early 1920s. The sudden increase in these players has coincided with a sudden drop in the players in the 130+ category. Only time will tell if this is a meaningful trend or a temporary blip. (As you can see on the graph, there have been many temporary blips in the past so it would be hasty to assume that this is not yet another one.)

- The two other groups, 110-119 and 120-129 have also remained fairly constant over the years. At first it seems odd that 120-129 has remained constant while 130+ has generally increased more and more. However, this is probably due mainly to the fact that the group 130+ covers a lot more ground, i.e. players with OPS+ values of (for example) 135, 170, or even 200. These data do tell us that there are a higher fraction of players in the highest group, but how each line compares to the other may have more to do with where I picked the cutoff values.

What does all this data tell us? When I originally thought of looking at these numbers, I expected to find a higher percentage of players hitting in the range 80-120 and few above or below. That's not the case. These data show us, quite definitely, that baseball has put an increasingly strong emphasis on offense by taking away at-bats from players under an OPS+ of 80 and giving them to players with an OPS+ of over 130. These are not, of course, one-for-one substitutions in most cases. It's not that teams demote a light-hitting good-glove shortstop in favor of another shortstop who smacks 40 HR a year (although that has happened in a couple of cases.) The changes are typically more gradual and institutionalized, as we have discussed on the comments in the earlier parts of this series. In the minor leagues, offense is stressed over defense. Shortstops these days are mostly guys who can hit pretty close to league average (at least) with virtually no examples of someone playing every day just for his defensive contributions.

Taking a larger view, you can split this graph into 3 phases:

- 1900-1923: Little change in percentages, all players clustered around 12%

- 1924-1950: Significant shifts as the percentage of 130+ OPS+ regulars goes up and under 80 OPS+ regulars goes down

- 1951-present: Little change in percentages with 130+ players at about 22%, under 80 players at about 5%, and all other players at about 13%

It seems to me that the shift away from defense and more towards offense happened primarily in the period 1924-1950. A number of the lines show some significant movement in the last few years but what does that mean? Only more time will tell.

June 21st, 2010 at 10:26 am

Great article series, very interesting.

I would like to see a similar one done on WAR levels through the years.

About how the percentages stay the same for the 110-119 and 120-129 groups while 130+ fluctuated, I would also add that as players move from 120-129 to 130+, 110-119 moves to 120-129, and 100-109 moves to 110-119, as the increases should be roughly approximately the same, as it appears to be an across the board movement.

June 21st, 2010 at 11:33 am

slighty unrelated, though kind of a response to #1:

why is WAR preffered by most everyone on this site as opposed to adjusted batting wins? they are essentially the same.(i feel like ive alredy asked this, but i cant find where)

June 21st, 2010 at 12:36 pm

WAR encompasses all of a player's contributions. Batting Wins is just batting.

June 21st, 2010 at 1:07 pm

Andy, is there anyway you can normalize this graph, like taking the ten year average for each year and plotting it, like you did in your previous OPS+ post per position.

June 21st, 2010 at 1:10 pm

As I mentioned above, this is 5-year averaged already.

June 21st, 2010 at 5:30 pm

The 80-99 range is very stable... a-ha. The Juan Pierre Zone lives!

June 21st, 2010 at 6:28 pm

I'm sorry if this is way off, but does that data show that less at bats are being giving to worse players OR players are just, on average, better at playing baseball?

June 21st, 2010 at 10:02 pm

XZPUMAZ - My take on that data is that players that perform poorly at the plate no longer receive enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting title. An interesting statistic to plot with this is the fraction of all plate appearances that are covered by players that qualify for a batting title. I would guess that it has fallen significantly over the past 80 years.